Awards

Design

Citation of Merit

Civic

The Design Citation of Merit is given for the restoration of Richards Medical Research Laboratories, one of the most important projects of architect Louis I. Kahn. This National Historic Landmark building retains a high degree of integrity and prior to the renovation it had undergone no major campaigns of alteration. Plagued with functional issues from the start, the building suffered from outdated building systems and the exquisite exposed concrete and cinder block walls and ceilings became so soiled and damaged that they had been covered up. This technically challenging renovation began with a change to the primary use of the building from wet lab science research to a dry-lab with computationally intensive uses. The key technical drivers of the restoration were glazing and the building systems. The dichotomy between sustaining the Laboratories as an architectural icon and its functional and environmental performance defined it for over fifty years. The renovation has resulted in a high-performance building admired by both the users and the local architectural community.

“The designers grappled with tough questions. What do you do with a problematic building greater in concept than execution? What should be ‘preserved’? We will face these questions again and the results here are valuable to study.”

-Alan Hess, 2020 Jury member

“The project integrates systems and technology while respecting the character of the existing, rigid structure and retaining character-defining features such as the window frames for a successful final design.”

The University of Pennsylvania

EYP Architecture & Engineering, Atkin Olshin Schade Architects

Primary classification

Terms of protection

Properties listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places must get approval from the Philadelphia Historical Commission for construction, alteration, or demolition through a design review process.

Designations

National Historic Register of Historic Places (as a contributing property to the University of Pennsylvania Campus Historic District), listed on December 28, 1978

Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, October 8, 2004

National Historic Landmark, designated on January 16, 2009

Author(s)

How to Visit

Location

University of Pennsylvania

3700-3710 Hamilton WalkUniversity of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, PA, 10025

Country

US

Case Study House No. 21

Lorem ipsum dolor

Designer(s)

August E. Komendant

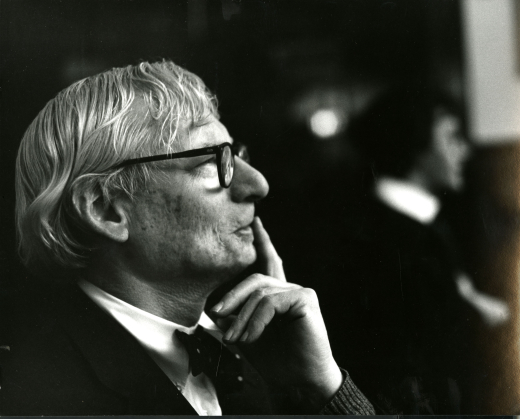

Louis I. Kahn

Architect

Nationality

American, Russian

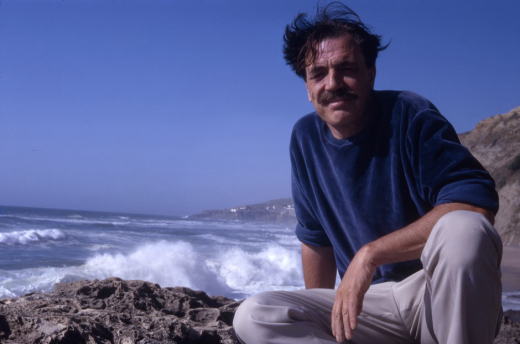

Ian T. McHarg

Landscape Designer

Nationality

American

Other designers

Landscape: George Patton (ultimately, his designs for the plaza were uncompleted)

Other designers: Dr. August E. Komendant (structural consultant); Atlantic Prestressed Concrete Co. (prefabricator); Keast and Hood (structural engineers); James T. Clark (electrical engineer); Cronheim and Weger (mechanical engineers); Fred S. Dubin (mechanical and electrical engineers); Joseph R. Farrell, Inc., (general contractor); additionally, for the construction of Goddard, United Engineers and Constructors were brought in to help complete the project.